It’s fun to have a mission.

I’ve been to the Tate Britain many times before but this was the first time I had a mission – I was looking for artworks that had representations of home in them.

Often I wander around museums and don’t really feel like I’m engaging with them. I did a short ethnography course a million years ago and the activity I undertook was watching others interacting with an artwork. Sitting there for an afternoon I felt quite exposed because, although I’d picked a quite well known and large piece of art to watch the watchers, most people passed it by very quickly indeed. My sitting there for so long felt very out of place compared to how long others were interacting with the artwork.

As someone who’s never learned ‘how to’ interpret art, I don’t feel like I come to it with a very wide vocabulary to understand what I’m seeing. That’s partly why I’m so interested in including reviewing different cultural materials in my PhD – it’s a way for me to learn some skills and approaches to understanding and interrogating artwork.

I love going to museums and galleries and enjoy exploring, so being able to get more ways to understand pieces of art and find ways to interact with them in a more meaningful way feels like such an enriching thing to be able to do. The fact that it’s in the service of something that feels useful in terms of answering the questions of my wider PhD then means I can allow myself to enjoy it without the more puritanical streak in me freaking out.

I also got to have some delicious tea and a lovely scone with an absolutely stonking amount of clotted cream and jam to refresh me part-way through the endeavour. If anyone had told me this is what working on the weekend could be like I think past me would find it as hard as current me to fathom this could be the case.

In that context then, I really enjoyed having that sense of purpose – being able to make my way around the exhibition with a hook to see what I could find. I also passed on my mission to the posse I was with which added to the fun, for me at least – I didn’t do a feedback poll to see how the others felt about it.

I had expected to be able to find more things along the way than I did though. Lots of pieces either didn’t seem to relate to the home or didn’t show people in that context.

Here are a few of the ones I did find along the way.

A fascinating piece, with such a story within it of the relationship between the two people. Virginia Woolf wrote an essay about Sickert, and particularly this piece, as a response. Albeit Woolf was writing in response to another version of the painting done by Sickert and held at the Ashmolean Museum – that one has much more vibrant colours and decor but the people within it are unchanged. Stuck and bored whatever their surroundings.

That sense of a story in the paintings comes through much more strongly in those pieces where there are multiple people in. From a Dr looking after a sick child, to men distraught – sometimes supported by their wife as in Hick’s work, at other times, as in Egg’s the prostrate woman is apparently the cause. Of course that also makes it harder to see the interiors though…

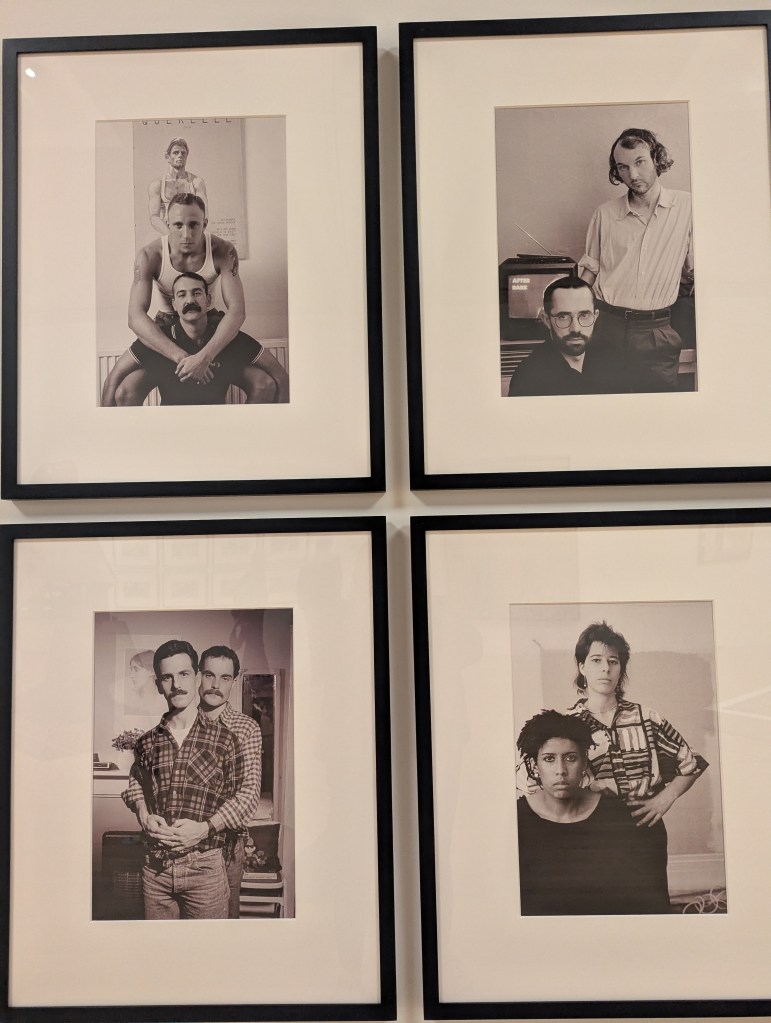

Woolf makes another appearance in the home of one couple in Gupta’s series showing homosexual couples at home. The photos were taken at a time in the 1980s when homosexuality was being portrayed as deviant whilst these photos present them as ordinary rather than other.

All of the paintings have a story to tell but from this collection of paintings at least, it’s a gentler story in those with just one person in. Peace, quiet and reflection in the scenes but, apart from McEvoy’s painting the interiors themselves are vibrant and busy – full of colour and objects.

More wandering and exploring, a beautiful richly coloured and empty view of the room where Shakespeare was apparently born; a side-quest visit to see the Henry Moore’s because I can still enjoy the stark, sensual beauty of them whilst working hard.

Then, as we left the building, we were met by Chris Ofili’s colourful, elegiac piece in memory of those who died in the Grenfell Tower fire. A totally different piece. The scale monumental compared to the smaller pieces I’d seen. Richly coloured and far removed from the gentle, quiet reflections. As with some of the other pieces, telling a story about when things have gone wrong, failings and harm. This time, at a societal level rather than between two people. The painting itself has a dreamlike quality about a nightmarish situation.

Only a few pieces of art found on my visit but that small selection shows just how varied homes and home-making and un-making can be, how fundamental they are to our lives and wellbeing.